“Overall, our results tell a consistent story,” Halberstadt added. "The fact that candidates with extremely well-fitting names won their seats by a larger margin - 10 points - than is obtained in most American presidential races suggests the provocative idea that the relation between perceptual and bodily experience could be a potent source of bias in some circumstances." "Those with congruent names earned a greater proportion of votes than those with incongruent names," said Barton in a released statement. They found that the candidates with the most shape-congruent names had received 10 percent more votes, on average, than those whose names were the poorest fit for the shape of their face. Their findings: Yes, people with “matching” names and faces are judged more favorably by others, and, yes, when those people are politicians, they tend to get more votes. That study, however, was actually a confirmation of research done decades earlier by the German psychologist Wolfgang Kohler who got similar results using almost the same shapes and the nonsense words “malumba” and “takete.”

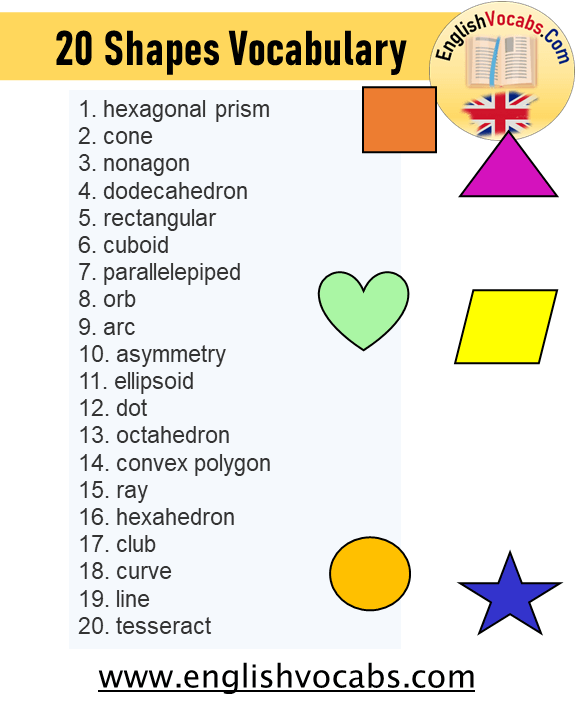

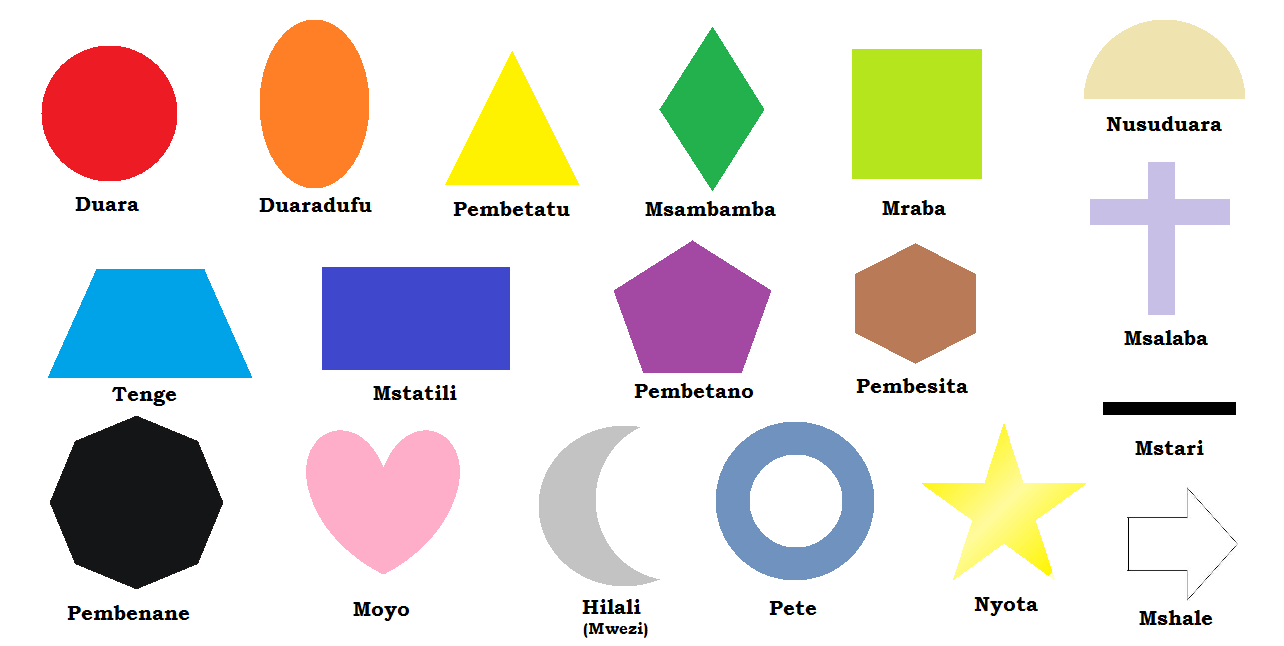

Researchers showed people two meaningless shapes - one round-edged, one spiky - and asked them to apply either the name “bouba” or “kiki” (both made-up words) to each.Ī solid 95 percent named the rounded shape “bouba” and the sharp-edged one “kiki.” The phenomenon gets its name from a study published in 2001. JVoters more likely to support candidates whose names ‘match’ the shape of their face, study findsīy Susan Perry | MinnPost contributing writerĪn intriguing psychological phenomenon is something known as the “bouba/kiki effect” - the tendency for people to associate rounded objects with names that require a rounding of the mouth to pronounce. Voters more likely to support candidates whose names ‘match’ the shape of their face, study findsīy Susan Perry | MinnPost contributing writer Face shapes produce expectations about the names that should denote them, and violations of those expectations carry affective implications, which in turn feed into more complex social judgments, including voting decisions.” “People’s names, like shape names, are not entirely arbitrary labels.

“The fact that candidates with extremely well-fitting names won their seats by a larger margin - 10 points - than is obtained in most American presidential races suggests the provocative idea that the relation between perceptual and bodily experience could be a potent source of bias in some circumstances.” “Those with congruent names earned a greater proportion of votes than those with incongruent names,” said Barton in a released statement. They then ascribed a face-name “matching” score to each of the candidates. The researchers had the roundness of the faces and names of 158 recent candidates for the United States Senate independently rated. In their final experiment, Barton and Halberstadt investigated whether the effect could be found in voting records. In other experiments, participants were found to express a more favorable attitude toward people whose name “matched” the shape of the face in the photograph - and a less favorable attitude when it didn’t. The participants assigned shape-congruent names, on average, to 14 of 16 round faces and 15 of 16 angular ones. The experiment was then repeated with photographs of male faces. The participants consistently matched nine of the 10 round faces with so-called round names (such as George and Lou) and eight of the 10 angular faces with so-called angular names (such as Pete and Kirk). The results provided strong evidence of the bouba/kiki effect. In their first experiment, Barton and Halberstadt asked participants (mostly young New Zealanders of European descent) to rank which of six suggested names went best with 20 overly exaggerated round or angular caricatures of male faces.

#Shapes and names series#

In a series of separate experiments, they examined whether the bouba/kiki effect leads people to think more positively about individuals whose names “match” their faces - and, if so, whether they then take that unconscious bias into the voting booth. All sorts of studies have been done on this phenomenon in recent years, including one published last week by psychologists David Barton and Jamin Halberstadt of the University of Otago in New Zealand.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)